Have you ever been so engrossed in an activity that time seemed to disappear, and your actions felt effortless and perfectly aligned? This profound state of immersion and focus is known as “flow,” a concept popularised by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi.

Also referred to colloquially as being “in the zone”, flow is not only about achieving peak performance in specific activities; it is also vital for our overall wellbeing and satisfaction in daily life. When we experience flow, we feel a deep sense of accomplishment and joy, which can significantly boost our happiness and reduce stress. Engaging in activities that promote flow can lead to personal growth, enhance our skills, and foster creativity.

In this article, we will explore the concept of flow, delve into real-life examples, and uncover how you can harness the power of flow to enhance your own experiences. Join us on this journey to discover the magic of what Csikszentmihalyi called “the ultimate human experience”, and learn how to unlock your full potential in any activity you choose!

Table of Contents

What is Flow?

A core concept in positive psychology, flow is defined as a pleasurable mental state in which a person performing an activity is fully immersed in a feeling of energised focus, full involvement, and enjoyment in the process of the activity. It is characterised by complete absorption in what one does and a resulting transformation in one’s sense of time (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2009).

As Csikszentmihalyi (1990) explains:

“The best moments in our lives are not the passive, receptive, relaxing times… The best moments usually occur if a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile,”

Flow can be found in many areas of life, from leisurely pursuits to repetitive work. Imagine a basketball player in the middle of an intense game, making precise passes and moving seamlessly with the team. Or consider a software developer writing code, engrossed in solving complex problems and watching their project come to life as each line of code fits into place. These are just a couple of examples of flow in action, where individuals are fully engaged, losing themselves in their activities, and experiencing a sense of control and exhilaration.

A Game-Changer in Positive Psychology

The concept of flow was first introduced by Hungarian-American psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi in the 1970s. Led by his interest in understanding what makes life worth living, he was fascinated by the phenomenon of optimal experience, observing artists and athletes who would become deeply engrossed in their work, lose track of time and experience a sense of natural control regardless of tiredness, discomfort, or hunger. He thus began to explore the characteristics of these experiences and the conditions that facilitated such deep engagement.

This research developed at a time where much of the field of psychology was focused on treating mental illnesses, especially in the aftermath of the wars happening in that period. Csikszentmihalyi’s work was thus pivotal in the development of the field of Positive Psychology, which sought to shift the focus from primarily addressing mental health issues to exploring and promoting the positive aspects of human experience.

The concept of flow demonstrated that happiness is not merely the absence of negative emotions but the presence of positive, engaging experiences, and Csikszentmihalyi’s findings encouraged psychologists to explore how people can cultivate such experiences to enhance their wellbeing (1997).

Flow also became a significant theme of one of Positive Psychology’s most well-known models of wellbeing, PERMAH. The element of Engagement directly relates to the concept of flow and is one of 6 components that contribute to a flourishing life, highlighting the value of flow states in our everyday wellbeing.

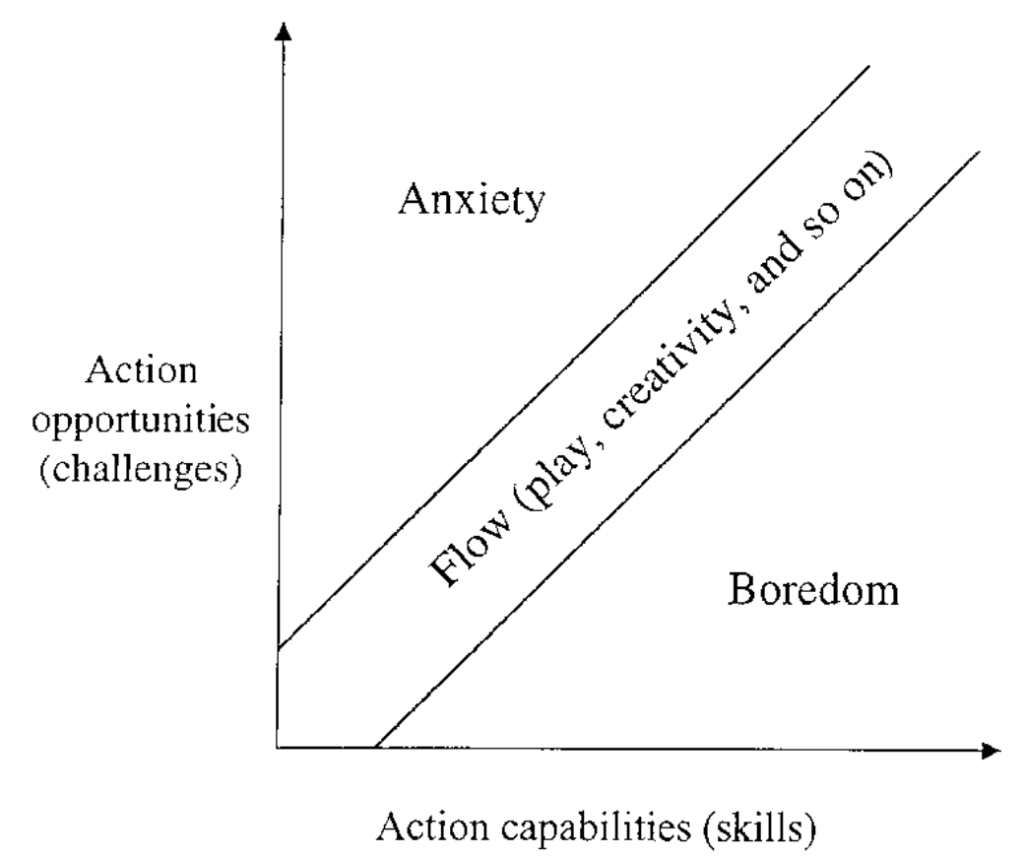

Visualising the Model of Flow

Unlocking the power of flow involves understanding and setting up the preconditions that facilitate this deeply immersive state.

Csikszentmihalyi’s flow model visually represents the relationship between the challenge level of an activity and the skill level of the individual. The simplified model on the left helps to show the ideal conditions for flow to occur, while the model on the right shows other emotional states that can arise when the level of challenge and skill are mismatched (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2002).

- Flow Channel: The flow channel is the optimal zone where the challenges match the skill level. When we operate within this channel, we are more likely to experience flow. This means that as our skills improve, we need to seek greater challenges to stay within the flow channel.

- Anxiety and Boredom: Outside the flow channel, activities that are too challenging can lead to worry, anxiety, or arousal (stress), while those that are too easy can lead to apathy, boredom, or relaxation. Understanding this balance helps us adjust tasks to maintain flow.

The Conditions for Flow

Flow is not just about being deeply focused; it encompasses several key characteristics that work together to create an experience of complete immersion and intrinsic motivation. By identifying these elements, we can better understand how to achieve and sustain flow.

Here are some practical steps you can explore:

- Set Clear, Achievable Goals: Define what you want to accomplish in specific terms to provide clear direction.

- Seek Immediate Feedback: Implement mechanisms to receive feedback on your performance, whether through self-assessment or external input.

- Match Challenges with Skills: Continuously adjust the difficulty of tasks to align with your growing skill levels. This is crucial, as many people wrongly assume that flow should be effortless. In reality, flow states require consistent adjustment.

- Allow for Loss of Self-Consciousness: Practice refraining from self-judgement so that you can become fully absorbed.

- Minimise Distractions: Create an environment that supports deep concentration and focus.

- Engage in Intrinsically Motivating Activities: Choose tasks that you find inherently enjoyable and fulfilling.

Several activities have also been found to help individuals cultivate flow by aligning with the necessary preconditions. Mindfulness meditation, for example, has been shown to enhance concentration and reduce self-judgement, thereby facilitating a loss of self-consciousness and deeper absorption in tasks (Kabat-Zinn, 2003). Regular physical exercise also contributes to better focus and mood regulation, supporting the mental clarity needed for flow (Ratey & Loehr, 2011).

Additionally, engaging in activities that promote intrinsic motivation, such as hobbies or creative pursuits, can significantly increase the likelihood of experiencing flow, as they align well with personal interests and provide inherent satisfaction (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Aligning activities with our character strengths can also further enhance the chances of entering a state of flow. People are more likely to experience flow when they engage in tasks that leverage their innate strengths. Identifying your sources of meaning is also crucial—when an activity resonates with your sense of purpose or provides deep personal significance, the potential for flow increases dramatically.

These research-backed practices can boost our ability to find flow in everyday activities by focusing on what naturally motivates and engages us.

The Key Characteristics for Flow

Now that we know how to foster more flow states in our lives, understanding what flow entails and recognising its presence in various activities can further enhance our ability to cultivate this optimal state more regularly.

How do we know when we are in flow? Look out for these key characteristics:

- There Are Clear Goals: Having specific, achievable goals provides a sense of direction and purpose, allowing individuals to focus their efforts on the task at hand.

- You Receive Immediate Feedback: Receiving feedback, whether internal or external, helps individuals adjust their actions in real-time, enhancing their performance and maintaining engagement.

- There Is Balance Between Challenge and Skill: The activity must be sufficiently challenging to engage the individual but not so difficult as to cause frustration. There needs to be a balance where the individual’s skills are well-matched to the demands of the task.

- You Are Concentrated on the Task: Deep concentration and focus on the activity are crucial. Distractions are minimised, allowing individuals to fully immerse themselves in the task.

- You Experience A Loss of Self-Consciousness: Individuals in a flow state often lose awareness of themselves and their surroundings, becoming completely absorbed in the activity.

- You Lose Your Sense Of Time: Time may seem to pass quickly or slowly, but individuals are usually unaware of the passing of time while in a flow state.

- You Feel Intrinsically Motivated: The activity is inherently rewarding, and individuals engage in it for the sheer pleasure and satisfaction it provides, rather than for external rewards.

It is likely that you already experience flow states in your life. Start to recognise them by looking out for the key characteristics and experiences of flow. Firstly, look for moments when you are deeply immersed in an activity, to the point where you lose track of time and are completely focused on the task at hand. Notice if the activity has clear goals that provide you with a sense of direction and purpose. It is likely something that you are skilled in, yet offers enough challenge to keep you on your toes. The task should be engaging enough to fully capture your attention but not so difficult that it becomes frustrating. When you find these elements coming together, you are likely experiencing flow.

It might be worth noting here that some activities are often mistaken for being flow state activities because they are enjoyable and cause us to lose track of time. These activities, like scrolling through social media or watching TV shows, typically involve passive consumption rather than active engagement and do not provide the balance of challenge and skill necessary for flow.

Next, we look at how to set ourselves up for experiencing flow states, exploring the conditions necessary for cultivating flow in our everyday activities.

Why Should We Cultivate Flow?

Being in flow states offers numerous benefits that significantly enhance overall wellbeing and performance. Research has shown that individuals who frequently experience flow report higher levels of happiness, creativity, and productivity (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). Flow fosters a deep sense of satisfaction and intrinsic motivation, as well as promoting personal growth as it encourages individuals to continuously develop their abilities and tackle increasingly complex tasks (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2002).

Flow has also been linked to improved mental health, reducing stress and anxiety by providing a sense of control and accomplishment (Fong et al., 2015; Engeser & Rheinberg, 2008; Mao et. al., 2020). These benefits of flow underscore why it’s valuable to understand and cultivate it for our overall happiness and health.

Going Further with Flow

As research on flow continues to develop, its applications and benefits are being increasingly recognised in various sectors, including education and organisational development.

In the realm of education, flow has been identified as a critical factor in promoting student engagement and learning outcomes. When educational activities are designed to balance challenge and skill, students are more likely to experience flow, leading to increased motivation, deeper learning, and greater academic achievement. For instance, research by Shernoff et al. (2003) found that high school students who experienced flow during classroom activities reported higher levels of interest, enjoyment, and intrinsic motivation, which in turn positively affected their overall academic performance. Educators can facilitate flow by setting clear goals, providing immediate feedback, and designing tasks that appropriately challenge students’ abilities.

Flow theory has also made significant inroads into organisational development, where it is used to enhance employee satisfaction and productivity. Work environments that promote flow can lead to higher levels of job satisfaction and lower turnover rates. Studies by Bakker (2005) and Demerouti (2006) have shown that job resources such as autonomy, feedback, and task variety can foster flow, resulting in better performance and wellbeing. Organisations that understand and implement these principles can create more engaging and fulfilling work experiences, leading to a more motivated and effective workforce.

Conclusion

In this article, we dove into the fascinating concept of flow, a state of deep immersion and optimal experience popularised by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. We explored what flow is, how it developed, and its impact on Positive Psychology.

Regular experiences of flow offer numerous long-term benefits that significantly enhance overall wellbeing, including higher levels of life satisfaction, increased creativity, and improved productivity. This makes it clear why understanding and cultivating flow is essential.

By implementing practical steps to intentionally enter flow states, we can transform mundane tasks into opportunities for growth and joy. This means that we not only make tasks more enjoyable but also create a foundation for sustained happiness and fulfilment.

We hope this article helps you find your flow and experience the profound benefits it brings to your everyday life!

References

Bakker, A. B. (2005). Flow among music teachers and their students: The crossover of peak experiences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66(1), 26-44. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2003.11.001

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Finding flow: The psychology of engagement with everyday life. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Demerouti, E. (2006). Job characteristics, flow, and performance: The moderating role of conscientiousness. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(3), 266-280.

Engeser, S., & Rheinberg, F. (2008). Flow, performance and moderators of challenge-skill balance. Motivation and Emotion, 32(3), 158-172.

Fong, C. J., Zaleski, D. J., & Leach, J. K. (2015). The challenge-skill balance and antecedents of flow: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(5), 425-446.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144-156.

Mao, Yanhui & Yang, Rui & Bonaiuto, Marino & Ma, Jianhong & Harmat, László. (2020). Can Flow Alleviate Anxiety? The Roles of Academic Self-Efficacy and Self-Esteem in Building Psychological Sustainability and Resilience. Sustainability. 12. 2987. 10.3390/su12072987.

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2002). The concept of flow. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 89-105). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2009). Flow theory and research. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Oxford handbook of positive psychology (2nd ed., pp. 195-206). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Ratey, J. J., & Loehr, J. E. (2011). The positive impact of physical activity on cognition during adulthood: A review of underlying mechanisms, evidence, and recommendations. Reviews in the Neurosciences, 22(2), 171-185.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78.

Shernoff, D. J., Csikszentmihalyi, M., Schneider, B., & Shernoff, E. S. (2003). Student engagement in high school classrooms from the perspective of flow theory. School Psychology Quarterly, 18(2), 158-176. doi:10.1521/scpq.18.2.158.21860