In 2023 and 2024, Singapore was ranked the happiest country in Asia in the United Nations’ World Happiness Report. But instead of celebration, the ranking sparked scepticism among many Singaporeans. Online discussions were filled with doubts, with some arguing that Singapore’s affluence did not equate to happiness. Comments ranged from sarcastic quips about rising costs of living to reflections on whether Singaporeans are simply “the least miserable” rather than truly happy.

The debate raises an important question: What does happiness really mean? Is it about comfort, financial stability, and access to opportunities? Or does it require something deeper, such as purpose, fulfilment, and meaningful relationships?

Psychologists have long studied happiness, and research so far has proposed two distinct but complementary lenses to understand it: hedonic happiness, which is externally derived from pleasure, enjoyment, and material comforts, and eudaimonic happiness, which comes from within—rooted in meaning, personal growth, and a sense of purpose. By exploring these two dimensions, we can better understand what it means to build a fulfilling life—and why a high ranking on a global report may not always align with personal experiences of happiness.

Table of Contents

The Science of Happiness

For centuries, philosophers, scholars, and psychologists have debated what it means to be happy. Is happiness simply the presence of positive emotions, or does it require a deeper sense of meaning and fulfilment? From Aristotle’s concept of eudaimonia to modern psychological research, the study of happiness has evolved significantly, offering different perspectives on how it can be understood and measured.

In psychology, happiness is often examined through scientific frameworks and empirical studies that attempt to quantify wellbeing and life satisfaction. This research has helped us move beyond abstract discussions to develop concrete models of happiness that can be applied to real life.

One of the most influential contributions to this field is Ed Diener’s (1984) work on subjective wellbeing (SWB), which measures happiness based on life satisfaction, positive emotions, and the relative absence of negative emotions. Diener’s research laid the foundation for understanding happiness as an individual’s perception of their life, rather than an external or fixed condition.

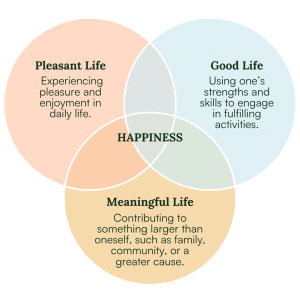

Another major contribution to happiness research is Martin Seligman’s (2002) work on positive psychology, which expanded the study of wellbeing beyond just positive emotions. He proposed that people can pursue happiness through three orientations:

- The Pleasant Life – Seeking pleasure and enjoyment.

- The Good Life – Finding engagement through one’s strengths and skills.

- The Meaningful Life – Contributing to something larger than oneself, such as family, community, or a greater cause.

Seligman then refined this model into the PERMA model, which highlights five key factors contributing to wellbeing: Positive emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment (Seligman, 2011). Unlike earlier models that focused primarily on happiness as an emotional state, PERMA recognises that flourishing requires a combination of positive emotions, deep engagement, strong relationships, a sense of purpose, and achievements that give life a sense of progress.

In recent years, scholars have proposed expanding PERMA to include Health and Vitality, highlighting the role of physical wellbeing in overall life satisfaction. While not officially part of Seligman’s model, this addition acknowledges that factors like sleep, exercise, and nutrition play a crucial role in our ability to thrive.

Happiness Across Cultures

Happiness is not a universal formula—it is deeply shaped by our values, traditions, and environment. What brings happiness to one person might not be as important to another, and cultural perspectives influence not only how people define happiness but also how they experience and pursue it.

A study by Oishi et al. (2013) found that older definitions of happiness across 30 nations often described it as good fortune or external success, whereas modern Western definitions focus more on inner feelings and emotional wellbeing. This shift highlights how different societies have understood happiness over time.

- In East Asian cultures, happiness is often tied to social harmony and balance rather than chasing personal achievement (Uchida & Kitayama, 2009). Success means little if it disrupts relationships or group unity.

- In contrast, Western cultures tend to associate happiness with individual fulfillment and personal success—achieving one’s goals and becoming the best version of oneself (Kesebir & Diener, 2008).

- Historically, the Ancient Greeks had yet another perspective—Aristotle’s idea of eudaimonia, where happiness came from living a virtuous life and fulfilling one’s potential. In medieval times, happiness was viewed as a spiritual blessing rather than something a person could actively pursue (McMahon, 2006).

Adding to these cultural insights, a systematic review by Singh et al. (2023) analyzed 155 studies on happiness across more than 100 countries and 44 cultures. Their findings identified three major determinants of happiness: Health, Hope, and Harmony.

- Health (mental, emotional, and physical wellbeing) plays a critical role in sustaining happiness throughout life, reinforcing the idea that happiness is not static but can fluctuate based on wellbeing.

- Hope (goal achievement, personal, and emotional growth) aligns closely with eudaimonic happiness, as it reflects personal progress and lifelong learning.

- Harmony (social, familial, cultural, and environmental factors) resonates with East Asian perspectives on happiness, where community and stability are prioritised over individual ambition.

Singh et al.’s (2023) research also supports the idea that happiness is not a fixed trait but a dynamic experience—one that evolves over time based on both internal and external influences.

Yet, across cultures, two fundamental ways of experiencing happiness emerge: hedonic happiness, which comes from pleasure and enjoyment, and eudaimonic happiness, which is rooted in meaning and personal growth. While some cultures may emphasise one over the other, both perspectives play an essential role in shaping wellbeing.

By recognising how different forms of happiness appear in our own lives, we can reflect on whether we are prioritising short-term pleasures, long-term fulfillment, or a balance of both—and what that means for our own happiness.

Happiness: Pleasure and/or Meaning?

From the perspective of happiness research, psychologists have long debated whether hedonic happiness, with its focus on enjoyment and comfort, is enough for lasting wellbeing, or whether true fulfilment comes from eudaimonic happiness—living with purpose and personal growth (Ryan & Deci, 2001). Some argue that hedonic happiness provides immediate gratification but fades quickly, while eudaimonic happiness creates deeper, long-term fulfilment. Others suggest that both are essential for a well-rounded and satisfying life (Delle Fave et al., 2011).

To better understand how these two types of happiness shape our wellbeing, let’s explore each in more detail.

Hedonic Happiness: the Pursuit of Pleasure

Hedonic happiness is the kind of happiness most people think of when they hear the word “happy.” It refers to pleasure, enjoyment, and life satisfaction—the feel-good moments that bring joy and comfort. Whether it’s savouring a delicious meal, watching a favourite film, or spending time with loved ones, hedonic happiness is about maximising positive emotions and minimising pain or discomfort (Kahneman, 1999).

In summary, hedonic happiness involves:

- Pleasure and enjoyment – Seeking experiences that bring joy, excitement, or relaxation.

- Life satisfaction – Evaluating one’s life positively based on achievements, relationships, and material wellbeing.

- The absence of negative emotions – Reducing stress, frustration, or discomfort to maintain a sense of contentment.

How Hedonic Happiness Contributes to Wellbeing?

Though sometimes viewed as superficial, hedonic happiness plays a crucial role in overall wellbeing. Positive emotions have been shown to:

- Reduce stress and improve physical health (Fredrickson, 2001).

- Boost life satisfaction, especially when experiences align with personal values (Diener & Seligman, 2004).

- Strengthen relationships, as shared enjoyable moments create social bonds.

However, it is worth noting that research on hedonic wellbeing found that while pleasurable experiences can temporarily boost happiness, the effect often fades due to a phenomenon known as the hedonic treadmill (Kahneman, 1999). This concept, first introduced by Brickman and Campbell (1971), suggests that people naturally adapt to changes in their circumstances—whether positive or negative—and return to a relatively stable level of happiness over time.

For example, you might buy a new car and feel on top of the world, vowing to keep it spotless and well-maintained. Yet, six months later, the excitement wears off, and the car becomes just another part of daily routine. This tendency to quickly adjust to new pleasures explains why constantly chasing external rewards may not lead to lasting happiness.

Thus, while hedonic happiness enhances life in many ways, relying solely on pleasure for happiness can be limiting. This is why psychologists suggest that wellbeing requires more than just enjoyment—it also involves meaning and purpose, which brings us to eudaimonic happiness.

Eudaimonic Happiness: The Pursuit of Meaning

While hedonic happiness is about pleasure and enjoyment, eudaimonic happiness is about meaning, purpose, and personal growth. It is the deep sense of fulfilment that comes from living in alignment with one’s values, developing personal strengths, and contributing to something beyond oneself (Ryan & Deci, 2001). Unlike hedonic happiness, which is focused on immediate gratification, eudaimonic happiness is about long-term wellbeing and self-actualisation.

Eudaimonic happiness involves:

- Purpose and meaning – Engaging in activities that feel significant and contribute to a greater good.

- Personal growth – Continuously learning, developing new skills, and striving to be the best version of oneself.

- Connection and contribution – Building deep relationships and making a positive impact on others.

How Eudaimonic Happiness Contributes to Wellbeing?

Though eudaimonic happiness may not always bring immediate pleasure, research suggests it is essential for long-term life satisfaction and overall wellbeing. Studies have found that:

- Living with purpose is linked to better mental and physical health, as well as increased resilience (Ryff, 1989).

- People who engage in meaningful activities experience greater life satisfaction than those who focus solely on pleasure (Steger, Kashdan, & Oishi, 2008).

- Acts of kindness and social connection enhance happiness by fostering a sense of belonging and fulfilment (Delle Fave et al., 2011).

Unlike hedonic happiness, which can diminish over time due to adaptation, eudaimonic happiness is more enduring. While pleasures fade, a life built on meaning and growth provides a deeper, more stable form of happiness (Waterman, 1993).

For example, consider someone who volunteers regularly at a community centre. While the experience may not always be enjoyable or easy, it provides a strong sense of purpose, connection, and fulfillment. Over time, this deeper meaning contributes to their overall happiness and wellbeing, and could even provide a remedy for burnout.

By understanding both hedonic and eudaimonic happiness, we can see that wellbeing is not about choosing one over the other—it’s about finding the right balance between pleasure and purpose.

What is Your Recipe for a Happy Life?

It’s easy to get caught up in the pursuit of instant gratification, or conversely, to push aside enjoyment in favour of achievement. But both pleasure and meaning are fundamentally important for our wellbeing, resilience towards stress, and overall mental health.

In Singapore’s cultural context, there is often a strong emphasis on eudaimonic happiness—where family, responsibility, and providing for others take precedence over personal enjoyment. If you tend to focus heavily on achievements and long-term goals, it may be helpful to reflect on how you can also make space for simple pleasures—whether it’s engaging in a hobby, spending time with friends, or allowing yourself moments of relaxation. These experiences may not always feel “productive,” but they are just as essential for a balanced and fulfilling life.

Perhaps this offers insight into why Singapore’s ranking as the happiest country in Asia was met with scepticism. While many Singaporeans have achieved success and security—factors often associated with wellbeing—their own definition of happiness may not align with how global rankings measure it. Is it possible that cultural expectations and social comparisons shape how people perceive their own happiness? Or that the pressures of a high-achieving society make it harder to feel the sense of contentment such rankings suggest?

Ultimately, understanding both hedonic and eudaimonic happiness allows us to make more intentional choices about wellbeing. By balancing pleasure with purpose, we can create a life that is not only enjoyable in the short term but also deeply fulfilling in the long run.

Happiness is not one-size-fits-all, and what works for one person may be different for another. The key is to cultivate awareness of what truly brings you happiness—both in the moment and over time.

References

Brickman, P., & Campbell, D. T. (1971). Hedonic relativism and planning the good society. In M. H. Appley (Ed.), Adaptation-level theory: A symposium (pp. 287–302). Academic Press.

Delle Fave, A., Brdar, I., Freire, T., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Wissing, M. P. (2011). The eudaimonic and hedonic components of happiness: Qualitative and quantitative findings. Social Indicators Research, 100(2), 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9632-5

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00501001.x

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

Kahneman, D. (1999). Objective happiness. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 3–25). Russell Sage Foundation.

Kesebir, P., & Diener, E. (2008). In pursuit of happiness: Empirical answers to philosophical questions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(2), 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00069.x

McMahon, D. M. (2006). Happiness: A history. Atlantic Monthly Press.

Oishi, S., Graham, J., Kesebir, S., & Galinha, I. C. (2013). Concepts of happiness across time and cultures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(5), 559–577. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213480042

Peterson, C., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: The full life versus the empty life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6(1), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-004-1278-z

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. Free Press.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press.

Singh, S., Kshtriya, S., & Valk, R. (2023). Health, hope, and harmony: a systematic review of the determinants of happiness across cultures and countries. International journal of environmental research and public health, 20(4), 3306.

Steger, M. F., Kashdan, T. B., & Oishi, S. (2008). Being good by doing good: Daily eudaimonic activity and well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(1), 22–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.03.004

Uchida, Y., & Kitayama, S. (2009). Happiness and unhappiness in East and West: Themes and variations. Emotion, 9(4), 441–456. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015634

Waterman, A. S. (1993). Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(4), 678–691. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.64.4.678